A DECISION

ADAPTED FROM MY BOOK 'I'M COMING TO TAKE YOU TO LUNCH', PUBLISHED BY UNBOUND, AVAILABLE FROM AMAZON

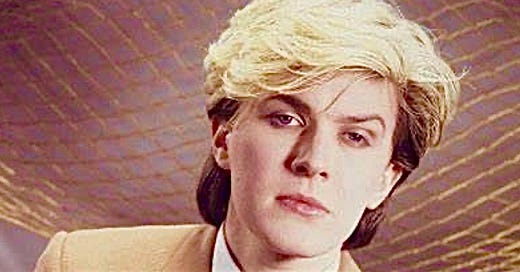

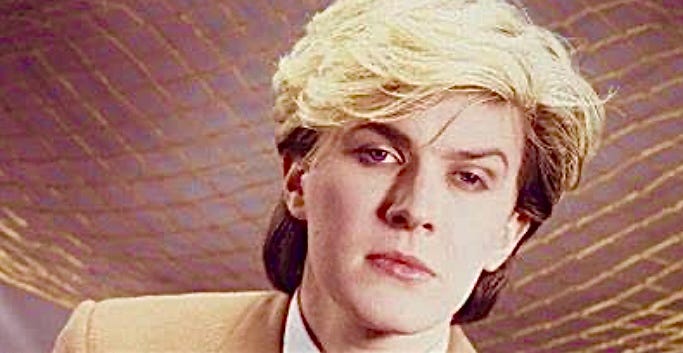

In the autumn of 1983, David Sylvian decided Japan had run its course. Shortly afterwards he went to Berlin to start making his first solo album.

At that stage I hadn’t yet decided whether to manage him as a solo artist or not, it was a difficult decision.

He'd told me, ‘In future I want to be like a minor Left Bank poet in post-war Paris – a celebrity but not famous.’

The trouble was - I had no interest in being a minor Left Bank manager. So I flew to Germany to listen to what he was recording.

He was at Hansa studios, in a slightly desolate area of West Berlin, just 100 yards from the Berlin wall. And the music he was making was beautiful.

Even so, it was deliberately uncommercial, dreamy rather than focused, with large periods of improvisation between rambling vocals. David's songwriting had lost its previous structured discipline.

When I got bored I wandered out of the studio to find I was in a cul-de-sac, dead-ended by the Berlin wall. There, overlooking empty roads and deserted houses on the other side, was a fifteen foot wooden staircase and a small platform. On it, people stood gazing into the East as if they were staring into the Grand Canyon or a nature reserve in Yellowstone Park. On the other side, although there was nothing to see, there was something to sense – a mist of cruelty, corruption and fear. Or was it just in the mind of the viewer? There was a strange smell too.

As I’d come up the stairs, I’d noticed at the bottom a man I thought might be a plain clothes policeman. I now realised he was selling drugs. Everyone on the platform was smoking, not normally but in a weird and private manner. But the smell wasn't the usual one of marijuana

‘What is it?' I asked one young man. ‘It's not grass, is it.'

'No!’ he shook his head. ‘It's heroin. You want some?’

'No thanks.’

After that I paid more attention. I couldn’t believe I’d missed it when I first came up the stairs. Some were smoking what looked like joints, presumably laced with heroin. Others sniffed smoke from powder placed on foil and heated with a match. Previously I’d been too intent on absorbing the atmosphere of the East to turn round and notice.

I asked one, ‘Does it fit well – the view – the atmosphere – the heroin?’

'The people I love most are on the other side. It hurts to stand here and think of them so I smoke to find comfort.’

How bizarre! This small viewing platform in a remote side-street of West Berlin had turned into a drug kiosk for escaped East Berliners – a perfect advertisement, really, for the freedoms of the West.

By the time I got back to the recording studio I’d made up my mind – David’s new album was too uncommercial – I would give up managing him.

It was a hard decision because over the previous seven years we’d been through a lot, often travelling together, just the two of us, without the rest of the group. One time we'd flown from Japan to Los Angeles to meet with Georgio Moroder who'd promised to produce the group's next single. We arrived and had a meeting with Giorgio who played us a selection of songs he'd written and asked David to choose one.

To Giorgio's surprise, David chose what was obviously the weakest of the bunch.

'Why, for heaven's sake,' I asked once we were outside.

'Because', he explained, 'it's such a poor song Giorgio won't mind if I re-write it. Whereas all the others are pretty good, which means I'd have a hard job injecting myself into them.'

David was nothing if not shrewd. And he couldn't have been more right. He re-wrote the song and called it 'Life in Tokyo'. Giorgio didn't even blink.

The following day I hired a car and we drove into the wooded hills behind Malibu. It was a dream of a day - spring-like weather, a Mustang convertible, and a wonderful collection of cassettes. We alternated choosing the next piece of music, trying to predict each other's tastes and picking what would best keep the ambiance flowing. We did it so well that even without speaking it felt like we were choosing as one.

There was one place we travelled to more than any other - Berlin - where Japan's record company was based - usually just David and I, there to do promotion without the rest of the band.

One time we arrived on the eve of an international soccer match and somehow didn't have a hotel reservation. The town was jammed, mainly with Scottish football fans, and we started asking at hotels in the back streets.

I knew it was going to be tough because David, as always, was plastered with make-up. I could never understand why. He wasn’t gay, he wasn’t even effeminate. 'Why d’you have to wear that bloody stuff?’ I asked him.

'It’s important,’ he said, which wasn’t much of an answer.

With David lipsticked and pansticked to the hilt, his hair rising above his head in a two-tone bouffant of blond and squirrel, we pushed through crowds of noisy Scots, drinking on the pavement. 'Tell us me lovelies, who takes the high road and who takes the low?’

It was amazing what a bit of lipstick on a bloke could drag from the lips of a Scottish soccer fan. ‘Och, the turd burglers are a-passing.’

We trudged from hotel to hotel, asking without much hope, ‘Any chance of a couple of rooms?’

Berlin was not the tolerant place it was to become twenty years later. At each place, as soon as the reception clerks saw us come through the door, they decided in the negative.

After the fourth or fifth hotel I began suggesting, ‘Just one room, perhaps? Just one bed?’ And by the sixth, ‘Maybe you could put a mattress on the floor behind the bar?’

Eventually someone mistook David for Quentin Crisp, whose life story had recently been shown on TV. The power of celebrity won. We were in.

But that had been two years ago and now it seemed we were about to separate. It was strange – while I’d never complained about any of the problems David’s make-up had caused me, it seemed I wasn’t prepared to stay with him through one uncommercial album. I wondered why?

I think it was a matter of objectives. While for me the principal objective had never been money, it was nevertheless an enjoyment of the process. I liked success, I liked creating a hit - I liked the game, the competition, the fun of winning, getting a number one.

But David no longer wanted that - in fact, he very much wanted to avoid it. So I decided that continuing to manage him wouldn't work. It was, after all, primarily a business arrangement. It wasn’t a love affair. It wasn’t about sticking with each other for life or staying together through thick and thin.

Even when you liked someone - even when you liked someone enormously - the job was still about business.

SUBSCRIBE AND LEAVE YOUR EMAIL - IT’S FREE - RECEIVE REGULAR PIECES

A wonderful piece and observation. I wasn't sure if you were involved with Japan during Tin Drum album -era. David and Mick Karn were such a great combination. The looks, as well as their sounds - it worked so well. And I'm a big fan of his solo work as well. And I do like Mick Karn's music. It's great history and its wonderful that you were part of it.

Great story Simon :-)