In April 1957, two days after my eighteenth birthday, I landed in New York at nine in the morning. America at last. The home of jazz. Everything I’d dreamed of since I was thirteen.

I was emigrating to Canada but had managed to book my flight by way of New York. I’d have forty-eight hours here before flying on to Toronto. In my pocket was the money I’d need when I got there - $50 - but what the heck! I wasn’t going to miss out on seeing New York.

The return bus fare into Manhattan was $3, which left $47 to spend on a hotel and jazz clubs. At the bus station on 42nd Street I put my large suitcase into left luggage and pushed my overnight stuff into a small bag. Then I walked to Times Square staring up at skyscrapers, beyond excited.

In Times Square there was an ugly concrete block of a hotel with a neon sign advertising rooms at $1.99. That would do nicely, though when I got to the room ‘nice’ wasn’t a word you could use. It was the last one in a corridor of cell-like doors, each with an iron grill covering it. Still - there was a bed, and a sink I could wash and pee in, and a shared bathroom in the passage outside. I used it, then went back into my room to put on fresh clothes. And that was it. Ready for New York.

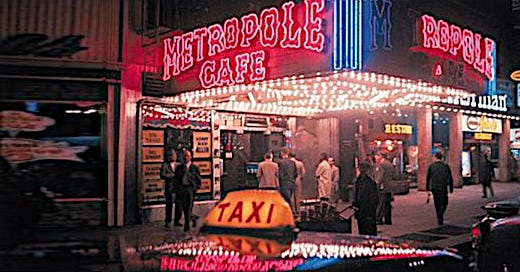

It was midday. I knew that on Times Square there was a twenty-four-hour jazz joint called the Metropole and I went straight to it. There was a long bar in front of a narrow stage where the musicians played. At this time of day there was just a house quartet. I’d read that in the evening every famous jazz player in America was likely to turn up and jam – from Miles and Dizzy to Ben Webster and Roy Eldridge.

I sat there for an hour over a 7 Up. Then spent an hour wandering around and found Birdland. Duke Ellington was playing that night and later I’d be back, but first I took the subway to the Village and sat for two hours over a five-cent coffee, just dreaming. New York on a Wednesday afternoon.

At 8pm, I was back at Birdland. I paid my entrance fee and found a seat next to the bandstand, right in front of the piano. To get in had only been $1.50 but there was an hour until the show and I had to buy a drink. I ordered a beer – not because I liked it, but because I didn’t, which meant it would last longer.

The show was heaven, like listening to all my favourite Ellington albums at once – but at ten times the volume. And magically, there in front of me were the actual musicians. For years I’d thought this didn’t actually exist, just something in the movies. But here it was.

Afterwards, if you were at a table eating dinner, you could stay for the second show. Where I was, you had to leave. But for the moment I stayed.

Duke Ellington stayed too. He was right in front of me at the piano, fiddling with some music. When the waiter came to tell me to leave, Ellington happened to glance up. ‘Did you enjoy the show, kid?’ he asked.

‘Amazing,’ I told him. ‘I’ve been listening to your albums for five years, but seeing you live was more than I could have imagined.’

Ellington spoke to the waiter. ‘Make the kid my guest,’ he said. So at 10 p.m. his band took me to paradise a second time.

Then it was out of Birdland and down the road to the Eddie Condon club on 52nd and 6th, another place I’d read about for years. Trad jazz this time, but brilliant, with Wild Bill Davison on trumpet. I tried to make my beer last as long as I had at Birdland but it seemed to be going down quicker.

After two of them it was midnight; time to go back to the Metropole. It was heaving. On the stage behind the bar was one of my favourites, trumpet player Rudy Braff – then Coleman Hawkins wandered in. Was this even possible? I was dreaming.

Here, there was no entrance charge but the drinks policy was strict. Once he’d checked my passport to make sure I was eighteen, the barman pushed me new ones every half-hour and demanded dollars.

The next morning I woke up in my $1.99 cell with a sizeable hangover. At eighteen, it wasn’t yet something I was familiar with. Most of my money was gone and I had just $13 left, but there was one thing I still had to do – go to the Harlem Apollo.

I had no idea how much it might cost to get in. I was also worried that I’d need money when I reached Toronto. Even if I found a job the same day, I’d still need the bus fare into town, and I also had to collect my suitcase from left luggage at the 42nd Street bus station. So I hid $10 under the chest of drawers and to save money set out to walk to Harlem.

It took two hours from Times Square to 125th Street and when I got there the artists performing were people I’d never heard of. Even so, I bought a ticket and the show was brilliant - two R&B acts, better than anything I’d ever seen before, and I sat through three shows - like cinemas, in those days, you could sit through as many shows as you wanted.

Then I had to walk back again. It was eight in the evening and I was hungry. I’d bought a burger when I arrived at the Apollo but that was six hours ago and now I was starving.

I had just five cents. Every time I passed a drugstore I’d look inside to see the food counter and at all of them the prices were the same – coffee five cents, buttered toast seven cents. I was afraid as I got further downtown the prices would go up so finally I went into one and asked the friendly black guy behind the counter how much two slices of toast would be without the butter. He gave me bacon, eggs, hash browns and coffee and wouldn’t even take my five cents. I said thank you. In fact, I said it so many times it made him embarrassed. But afterwards I still worried I hadn’t said it enough. And I still do.

There’s no good way to say thank you properly when someone is that kind.

CLICK & LEAVE YOUR EMAIL - GET REGULAR NEW PIECES - IT’S FREE

I felt like I was there Simon, I could taste that flat beer ... Thank you 👏

Thanks for New York, 1957... I wish I could have done that trip like you did then if only at those prices but more so catching those shows with those performers... Ellington and all!