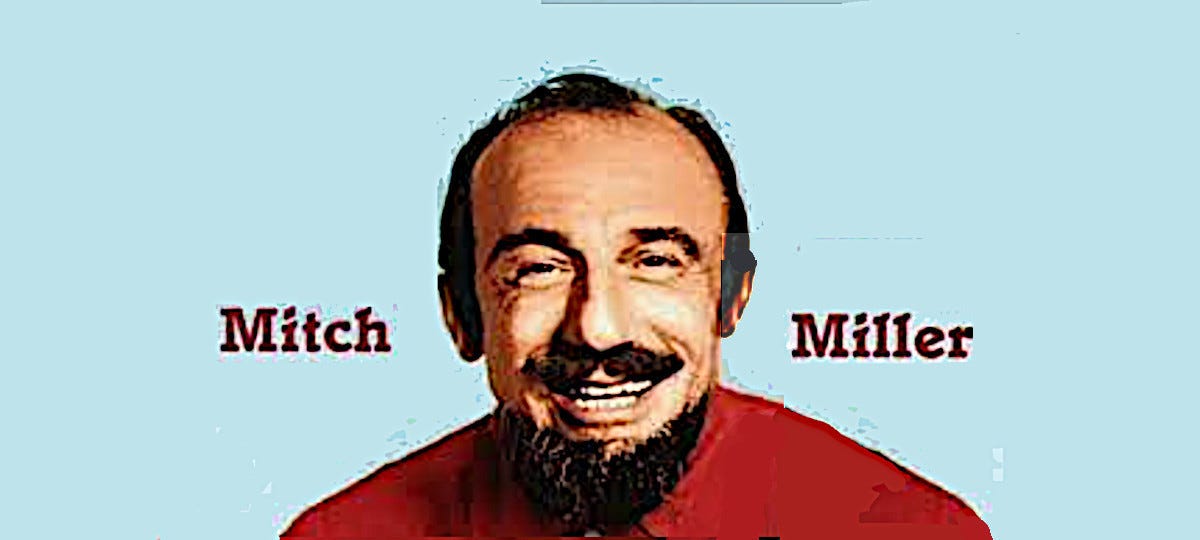

THE GHASTLINESS OF MITCH MILLER

FROM MY BOOK ‘THE BUSINESS’, PUBLiSHED BY UNBOUND BOOKS/ (WITH THANKS TO WILL FRIEDWALD}

In Britain at the beginning of the fifties there was no rock ’n’ roll, the word teenager didn’t exist and British pop music was trash.

Post war Britain was gloomy. There was rationing, unemployment and bad housing. More than half the homes in Britain had outdoor toilets and almost none had central heating. There was no entertainment for young people and over and over again they had to listen to their parents say, “We fought the war for you.”

The music industry was still focused on selling sheet music. People bought the latest pop song and struggled through it on the piano at home. Broadcasting was controlled by the BBC and because of an agreement with the musicians union there were only ten hours each week during which pop records could be played. Listening to the current hit records meant staying awake till 11pm on a Sunday night when the Top 20 was broadcast by Radio Luxembourg, fading in and out from 208 on the medium wave.

It wasn’t aimed at teenagers; it was aimed at young marrieds. Radio Luxembourg’s Top 20 was sponsored by Horace Batchelor, a man with a droning West Country accent who guaranteed listeners they could win the football pools if they followed his system. But here’s the point – Horace Batchelor had picked the Top 20 for his hourly week of advertising, yet the football pools were forbidden to anyone under twenty-one. That summed up pop’s target audience – twenty- one to thirty-five. The songs were dreadful, with corny melodies and excruciating lyrics. And they nearly all came from America.

For America, the end of the war had meant the start of television. Its programmes projected a country of extraordinary conformity. Everyone wanted social cohesion, especially advertisers. For them, a perfect society was a homogenous one and advertising agency J. Walter Thompson led the way by using 7up ads that played on people’s fear of rejection and their desire to fit in. “You like it – it likes you”.

The images were of smiling welcoming people; society, they told us, was one big happy family. But since the family projected was totally white and middle-class, it was difficult for anyone who wasn’t one of those two things to see where they fitted in.

To frighten them into trying anyway, and to induce even greater conformity, Americans were told they faced a common enemy in communism. The country was liable to attack at any minute; underground air raid shelters were built at schools and students were drilled in what to do in case an atom bomb was dropped. Then along came Senator McCarthy.

McCarthy was intent on branding as many people as he possibly could as ‘commies’. He ran Senate investigations on anyone he could get his hands on, from show-business stars to average office-workers, searching out anyone who might once have had left-wing sympathies. For seven years Americans conformed, afraid not to do so. And conformity included popular music.

The singers were Guy Mitchell, Frankie Lane, Jo Stafford, Doris Day and Patti Page. The songs were ‘Mule Train’, ‘She Wears Red Feathers’, ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky’, and ‘Shrimp Boats is-a Comin’’. They were cheesy and crass; popular music had never been more unlistenable. Even so, some songs managed to sound worse than others, and if they did they were probably written by Bob Merrill. His hits included ‘If I Knew You Were Coming I’d Have Baked a Cake’, ‘She Wears Red Feathers’ and ‘How Much Is That Doggie in the Window’. Bob Merrill had a magic touch for the truly appalling.

So did Mitch Miller, head of A&R at Columbia Records. Miller had been an oboe player, a conductor, a choral director, and a school friend of Goddard Lieberson, Columbia’s new president (who liked to sign his letters ‘God’). Lieberson had put Miller in charge of Artists & Repertoire, making him the man who chose the artists and the songs they would sing. And Miller’s taste was pure kitsch. He was also Columbia’s chief record producer, and therein lay the problem, because his productions were horrendous.

Since its invention the microphone had been like an ‘audio camera’ capturing magic moments of sound – a great performance by Caruso, a brilliant improvisation by Charlie Parker, a perfect rendition of a ballroom performance by the Glenn Miller Orchestra. It was a musical snapshot of what you would have heard had you been there. But Mitch Miller didn’t use the microphone for capturing magic moments; he used it for creating them.

Miller’s records were not recordings of a performance, they were original works in their own right, works that didn’t exist before he created them in the studio. “To me, the art of singing a pop song has always been to sing it very quietly... in other words, the microphone and the amplifier made the popular song what it is – an intimate one-on-one experience through electronics.”

The way he describes it makes it sound as if his records were wonderful when in fact they were the record equivalent of plastic gnomes in the garden. Despite that, he has to take credit for inventing the modern pop record – a unique work of art created in the studio.

Mitch Miller made the recording process a new creative art. There was the song, the arrangement, and the vocal interpretation. Now there was also the recorded sound, quite different from how it would have sounded had you been there. Quiet instruments became loud, loud ones became quiet, and sound effects were added – whips, cowboy whoops, bells or animal noises. The end result was not so much an arrangement of a tune, but an aural representation of the story of the song, which might have been wonderful if Mitch Miller had possessed the merest hint of good taste. Instead, everything he touched became truly abysmal.

Music critic Will Friedwald summed it up perfectly. “Miller chose the worst songs and put together the worst backings imaginable – not with the hit-or-miss attitude that bad musicians traditionally used, but with insight, forethought, careful planning, and perverted brilliance.”

Another person who hated Mitch Miller’s production style was Frank Sinatra. “Before Mr Miller’s advent on the scene I had a successful recording career which went into decline.”

Miller had signed Sinatra then fallen out with him. Sinatra had stormed out of the studios and left the label, saying due to taking bribes Miller was choosing inferior material. It wasn’t true, but it was certainly true his productions weren’t right for Sinatra.

Each time Mitch Miller stepped out of his office at CBS he would find himself on 52nd Street. For nearly ten years it had been the home of bebop. From end to end, the street was crowded with clubs and musicians. Charlie Parker, one of bebop’s originators, said, “Music is your own experience, your thoughts, your wisdom – if you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.”

If the music that came out of Mitch Miller’s horn was a distillation of his life, it must have been a sad one indeed. And that was the problem. His records were nothing to do with his life. He was a classical musician and when asked to produce popular music, he did it with disdain. He was equally disdainful of Frank Sinatra. “Take away the microphone and Sinatra and most other pop singers would be slicing salami in a delicatessen.”

It was difficult to put a finger on what made everything he touched so resoundingly awful, but there’s a surprisingly good quote from Miller himself that perfectly describes his productions – “musical baby food... the worship of mediocrity”.

Unfortunately, that’s what he himself said ten years later about rock ’n’ roll.

CLICK SUBSCRIBE AND LEAVE YOUR EMAIL - YOU GET A PIECE A WEEK

That, sir, is the prose equivalent of a hit single. 2 minutes of distilled brilliance. To paraphrase Queen, "Mitch Miller, he will not let you go".

I love your musings on modern music history! Very informative Simon :)